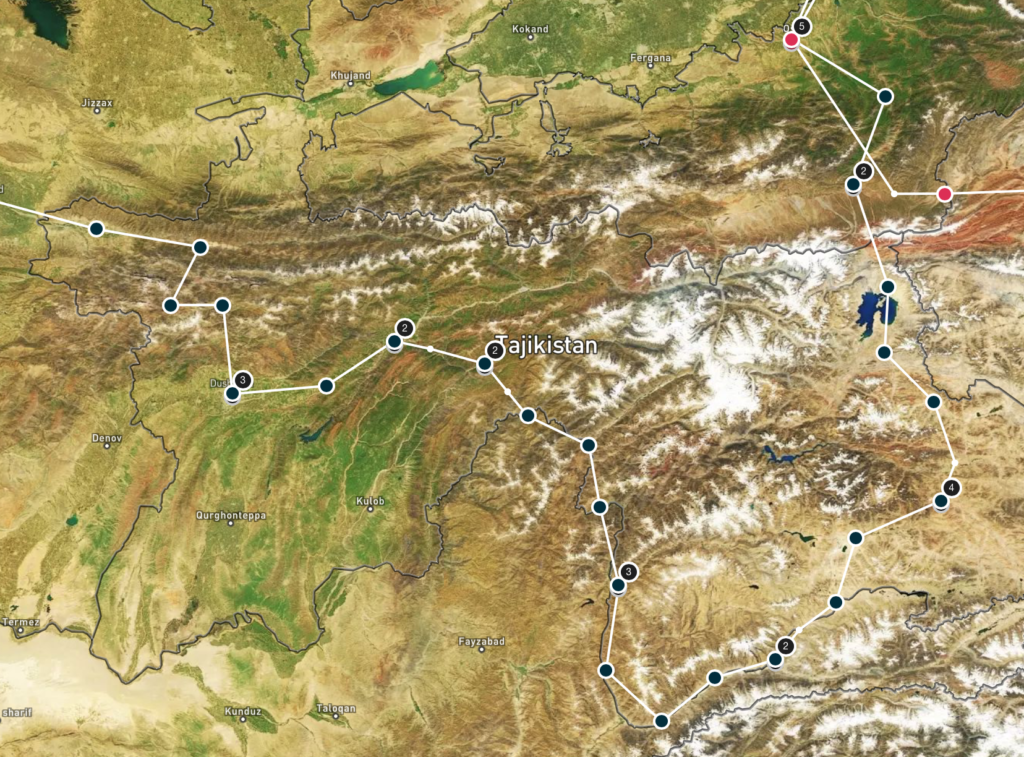

Panjakent (TJ) – Sary Tash (KG) / 9110 km / 4.44 Million Turns / July 19th – August 21st, 2019

“HELLOOOO WHAT IS YOUR NAME!!!!!???”, some Tajik kids are shouting from the top of the hill and from the top of their lungs. With a big smile we answer and ask their name in reply, but the response “BYE BYEE” assumes the conversation won’t be long. Tajik kids already earned the trophy for most enthusiastic people met along our trip on Day 1. This fact surprised us quite a bit actually, since Tajikistan, especially in summer, is ‘crowded’ with cycling tourists. But still, each and every single cyclists is met with high-fives, ‘what-is-your-name-shouts’ and big smiles as if they are the very first cyclist the kids see. Welcome to Cycling Walhalla, welcome to Tajikistan!

It seems that when Uzbekistan and Tajikistan drew the border between their countries, they must have done some kind of exchange. Uzbekistan would get all the flat land and melons, while Tajikistan in return was allowed to keep all mountains. As such, cycling the last few km towards the Uzbek-Tajik border, it was quite clear where the border was. Right in front of us, a towering wall of rock greeted us. Delightful after so many weeks of flatness, we were ready to do some climbing again.

Tajikistan, for non-cyclists probably a country hard to point out on a map. The main draw for all the cyclists is the so-called ‘Pamir Highway’ or, more matter-of-factly, the M41. It crosses the Pamir plateau, which in Ancient Persian loosely translates to “Roof of the World”. The Highway was built by the Russian army in the time Tajkistan was still part of the Soviet Union, it used to be a highly strategic military road. After the Soviet Union collapsed, so did the road (in a literal sense). Crumbling down under the stress of hot summers, cold winters, snow, rain and heavy trucks, the road in some places more resembles a 4WD track than a proper highway. Fortunately, exactly that draws so many overlanding (car, motorbike, cycle) tourists towards it. As it straddles the Afghan border, it winds itself up a high plateau more than 4500 m high where it feels as if you have abandoned Earth and landed on a Mars-like alter-ego planet.

However, before you reach the starting point of the Pamir Highway, the capital city Dushanbe, you still need to cross the Fann mountains, which means ‘only’ climbing to nearly 3000 m above sea level. Fortunately, we joined forces again with Sarah and Pedro with whom we also cycled in Iran for a bit. We were all so eager to climb mountains again that we even made a 30 km detour to the Iskanderkul lake. Other cyclists and guidebooks stated it was an alpine oasis with crystal blue waters surrounding by nothing more than peace and tranquility. Unfortunately, things in practice turned to be a bit less utopian. Heavy construction ruined most of the tranquillity and turned the water murky grey. Also, the most aggressive mosquitos ever made camping quite a challenge. The road to the lake however was nice, and apparently the lake is a lot more beautiful in autumn (hint to other cyclists who think of visiting the lake).

Dushanbe, a surprisingly green city, would be the place to prepare for the month of barrenness ahead. As it has multiple large supermarkets, including a franchise of the French Auchan, we found everything we needed essential to survive the Pamir: red wine, French cheese, Italian pesto…. Oh and some other nice-to-haves of course such as pasta, porridge and toilet paper. In Dushanbe, we were also reunited with our drone, which we sent over from Georgia and miraculously arrived as it should have, within the set time, in good condition and on the correct address.. we were amazed.As said, from Dushanbe, the actual ‘Highway’ starts, but many cyclists set off from Dushanbe taking the so-called South route, which technically is not the M41. However, this route is a lot more ridable as the tarmac is new and the climbs less high. The more ambitious (crazy/masochistic?) cyclists take the North route however, the ‘true’ Pamir Highway. One little problem is that most of the way is unpaved, recent landslides covered some segments in just dried-out mud and oh yeah, forgot to mention it, there is also a 3300 m mountain pass to cross. Other than that, it’s a walk in the park. By now you might guess which route we took…

Fortunately, the North route turned out to be a great choice. Yes, it takes a bit more time, but traffic (and as such dust) is less, we had some splendid camping spots along the way and the views, especially going down from the 3300 m pass were all worth it. During the descent here, you’ll first ride through a canyon with the river roaring 150 m vertical drop straight down. As you exit the road on this high ridge, you follow a crystal-clear river (a bit of compensation for Iskanderkul) to the town of Qalai-i-Khumb, where you join up with the South route and hit the border river with Afghanistan. From here, all cyclists reunite, and the true Pamir experience begins.

The road from Qalai-i-Khumb to Khorogh, the next town on the Pamir Highway, turned out to be even worse than the North route previously. Yes, it was (had been) technically paved, but only islands of asphalt remained. Mostly, it was a mixture of loose rocks, sand, washboards and other unidentifiable road types. The road gradually climbs from 1200 to 2000 m but does so in a very ‘inefficient’ way. We easily did more than a 1000 altitude meters up daily but at the end of the day ended up only 300 m higher then where we started. As such, this stretch took quite some energy of ourselves and tested the bikes as well. Although nothing broke on this part of the route, gear was tested to the limit. The road follows the Panj river here, which also denotes the border with Afghanistan. We followed the contour of this infamous country for more than 2 weeks. It was quite strange to peek into a country so much in the news (negatively). However, not many odd things happened; people were busy living their village lives, tending the land, leading their donkeys. This part however is also relatively safe; and it makes you realise a country is often not a single entity but many different people, regions and cultures can all have very different lives in a single nation. (OK disclaimer, we did hear one gunshot at night….)

After 9 days of cycling out of Dushanbe, we reached Khorogh, where we would restock on our food supplies and take some rest. Unfortunately, no Aushan here, and so no more red wines. it was hard even to find the basic needs but by visiting several shops and the local bazaar we managed to find all we needed in the end. From Khorogh, we had another decision to make: continuing along the regular M41 or doing the detour in the Wakhan valley. The same principles apply a bit here as with the North/South route choice, but then x10. The Wakhan is famous for its history, culture and natural beauty but has notoriously bad roads. “Is it worth it?” is the most asked question at the Pamir Lodge guesthouse in Khorogh.

In the end, the most accurate way to answer the question above is to see it for ourselves, we thought. With a healthy dose of weariness of what was to come, we set-off into the Wakhan. Although the first day was a bit more of the same as we had before Khorogh, we quickly saw what lured people to take this detour. The valley opened up and widened, with majestic 7000+ m high peaks becoming visible. These peaks were part of the Hindu Kush range bordering Pakistan and Afghanistan. As such, we could not only see Afghanistan, here for the first time we peeked right through the country. At some places the Afghan part of the Wakhan is only 30 km wide (Note for history geeks: This appendix-like region of Afghanistan has only been part of the country for a few hundred years and was meant as a buffer zone to safeguard peace between the British Empire (Pakistan) and the Russian Empire (Tajkistan)).

The road in the first section of the valley was quite good actually, resulting in attractive cycling. However, mid-way, at the village of Langar, we hit upon what people warned us for: washboards. If there is any road surface a cyclists chooses to ride, washboards will probably finish last. It feels like every screw on your bike loosens up and every organ in your belly is turned upside down. There is a certain threshold speed at which you literally fly over the corrugations and riding becomes relatively comfortable, but those speeds of ~80 km/h per hour are only attainable for cars and motorbikes unfortunately. It leaves no other options for cyclists than wobble over the road and hope the worst sections end soon.

Langar also is the last town of the Wakhan; for three days we see no other village or shop. The only other people we meet are other tourists (of which there are actually quite a lot). The nothingness around is what makes it so beautiful here, nothing but ten different shades of grey and brown of the different rock types. Some New-Zealanders we met marked their experiences by Type A or Type B fun (resp. fun now and fun later, and not fun now but only fun later). The Wakhan definitely was Type B fun. We were exhausted when finally re-joining the perfect asphalt of the M41 and exiting the Wakhan. It took its toll, on us, on the bikes, on the drone and on a lot more stuff that broke down there. We rode the last 25 km to the nearest village where we stayed in a homestay and enjoyed the ladies’ freshly made yoghurt (nearly 3 litres in total, that is) to recover.

From here, the road surface would get better. However, it wasn’t the Pamir if a new surprise came around the corner. Goodbye washboards, hello headwind! We were now high on the plateau (above 4000 m mostly) and the wind was master and commander here. After another few rest days in the town of Murghab, the final stretch of Tajikistan lay ahead of us. In this region, the Pamir Highway reaches its highest point, Ak-Baital pass of 4655 m above sea level.

Getting higher and higher, the landscape got even more desolate, Tajikistan really is a country of superlatives. Although most of the climb up to the highest point is fairly easy, the thin air at altitude, battering headwind and steep last section still made it a challenge. Reaching the top of the pass was a definite highlight for us! We celebrated together with a Belgian family travelling with 3 children by truck, who reached the top at the same time as we did. Cosily tucked away in the back of the truck, we had homemade cous-cous salad and apricot jam for lunch, while outside the wind was blowing like a madman.

Coming down from the pass, there was one final highlight en route: Lake Karakul. The lake, once created by a giant asteroid, has so many shades of blue it is hard to describe why it’s beautiful. All around the highest mountains of the Pamir region rose in the background, and there was just nothing except for the road and a tiny settlement. It’s very hard to capture the beauty of the place in pictures, let alone words. The morning we cycled past, the wind was still snoozing, so we gladly made use of the wind-free window to fly our drone in all directions (now working again thanks to superglue after the Wakhan crash). After our final (again windy) night in Tajikistan, we left in freezing conditions and entered country #15 already, Kyrgyzstan! As some Swiss bikepackers in Murghab stated: “Cycling in Kyrgyzstan is heaven on Earth, cycling in Tajikistan is heaven on another planet”.

More on our Kyrgyz’ adventures in our next blog!

Talk to you soon!

Tom & Sabine