Huay Xai (LS) – Nongchan (LS) / 16380 km / 7.99 Million Turns / January 10th – February 2nd, 2020

Each time we enter a new country, we have certain ideas about it. Some of these ideas are based on previous experiences we had on different trips, some are based on the internet, some on stories from people we met, and some based on …. nothing really. In some countries we expect to see a specific type of nature, in others we read about a certain local dish that’s either the best or really gross, in yet other places we heard that people wear a specific type of clothing. As it goes with expectations, some of them might be true, whilst some might take you totally by surprise and turn out the opposite of what you had made of it in your mind. We read about Turkey having a higher level of hospitality compared to the previous European countries we had visited on this trip, but it even exceeded our expectations. We thought that the roads in Kyrgyzstan would be perfect gravel, which meant great off-road cycling. Instead we got training after training of keeping our heads cool while bumping our way through on the washboard-filled roads, feeling our brains shake against our skulls.

Our idea for Laos was mainly that this was to be our “holiday cycling part” of the trip. After a couple of challenging countries with all sorts of restrictions – may it be extremely busy roads with either dangerous and/or deafening honking behaviour of the drivers, camping being either impossible or illegal or cycling with long sleeves/trousers in the pressing moisture heat of jungles because of cultural reasons – we were really up for some easier cycling. We heard that Laos had tons of (quiet) off-road cycling, friendly people and beautiful waterfalls near Luang Prabang. Foodwise we didn’t have high expectations for Laos. However, the Beerlao (the national beer) would make up for that. Sabine knew the brand from a previous backpacking trip and had been tempting Tom for months about this (especially in the alcohol-free countries of Islamic Asia), saying it is one of the best lager beers she had ever had. Lastly, we had read on several other people’s blogs that Laos is quite hilly and that the roads could be steep. Somehow that last part about the hilly roads had not really penetrated deep into our brains/expectations, and we still assumed that it couldn’t get any steeper than in some parts of central Asia. Boy, were we in for a treat!

Now borders crossings are never a good representation of a country, and the crossing at Chiang Kong (Thailand) to Huay Xay (Laos) was no exception to this. On this specific border, customs employees had decided that for all kinds of small things they would collect a few dollars from tourists. If one wants to cross the border before 8 AM or after 4 PM, you pay a dollar for the “out of office hours” crossing. Another dollar has to be paid for crossing the border in weekends. If you cross the border in the weekend and outside of the office hours, you actually pay two dollars extra. And then there is the mandatory bus ride of 2 km across the border river. The price of this ride was half the price of our overnight bus ride from Bangkok all the way north to Chiang Mai (about 700 km), and the price to put our bikes on the bus was 5 times the price for our own seat. Us stubborn travellers don’t really like these kinds of practices, so on our last long day in Thailand we pushed ourselves to arrive at exactly 3:58 PM at the border, so as not to pay their funny outside-office-hours fee. After some sputtering – to no avail – we paid for the mandatory bus ride, crossed the Mekong river, made a switch in driving lane (again, as Laos was a French colony and thus drives on the right), and a whole one minute later we found ourselves on Laos soil! By then the sun was starting to set, and we quickly started to search for a camp spot. In spirit of our hopes for some holiday cycling, we found a beautiful spot overlooking the mighty Mekong river and Thailand on the other side. Sitting there on our comfy little camping chairs, with two cold Beerlao we had managed to find on the way, we rejoiced over the start of our holiday cycling leg in Southeast Asia. Tom easily agreed with Sabine on the beer-expectation for Laos.

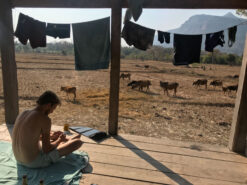

Our camping spot was a little bamboo hut. Farmers build these to take shade from the sun (or rain in monsoon times) during breaks from their work. They come in all sorts and sizes, some made from thin bamboo branches and only 1.5 m high with a roof made of bamboo leaves, others professionally built from sturdy wooden planks and tin roofs, so big in size you could arrange specific “rooms” in it. Yet others have two plateaus and come with stairs in it. The good thing is they all have a plateau to sit (or sleep) on above the ground, so as to be safely away from the insect/snake/scorpion ridden ground. We did not need the roofs for protection against rain (we were there in the dry months), but they kept our stuff dry from the intense morning dew that we were going to face almost every single day. The main advantage however, was that because we were above the ground, we wouldn’t have to set up our tent. Our tent, even if we set up only the inner tent, is quite warm. In the hot summer months in central Asia, we often found ourselves floating in sweat in the nights. Foreseeing another episode of this in the hot and humid climate of southeast Asia, we had bought ourselves a big mosquito net and a bit of rope to attach it, to protect ourselves against not only mosquitos, but also other creepy crawlies. On a few occasions we found big spiders and even a couple of scorpions and a nest of aggressive hornets in the bamboo huts, the mosquito net kept us pretty safe from those. We first encountered these little huts in northern Thailand, and they quickly became our favourite places to sleep. The search for the perfect hut would occupy our minds for many hours on the bikes. Sometimes we would even stop a few hours early if we found “the perfect hut” with good views over a valley, or a big firm plateau with enough space to dedicate one area to cooking and another to our bags and sleeping.

Our first goal was to cycle towards Luang Prabang on mainly small dirt roads. We had missed these, especially after large parts of India, Nepal and Myanmar had led us over busier roads. We decided to separate from the main road from Huay Xai to Luang Prabang and follow the Mekong river for a few days, on a quiet dirt road. “Dust road” would have been more suitable to describe this road, as the upper 5cm of the road consisted of layers of the finest dust that would fly up in the air with the lightest breeze. You can imagine how we looked after a few days of cycling through it (without a shower), putting layer upon layer of sweat, dust and sunscreen on every uncovered part of our bodies! Fortunately, our looks did not scare away the people. Laotian kids were some of the most enthusiastic ones we have met on our ride. As soon as they would notice us appearing, many would come running towards us screaming “SAABBAAAAIIDDDEEEEEEEE” on the top of their lungs! It’s great to see how curious these kids are and often they were quite keen to name all the countries from the flags we had on the back of our bikes.

The road was tough, but it offered stunning views over the Mekong, close to zero other traffic, and a look into rural life in Laos. It wasn’t hard to see that compared to Thailand, Laos is a lot poorer. Instead of steady brick or concrete houses in Thailand, here we saw most of the houses made of wood or bamboo with tin corrugated roofs. It always surprises us how big socio-economic differences like these can be over such a little distance, Thailand was less then 10 km away!

Taking this route had been a bit of a gamble. At some point we had to cross the big Mekong river, but different maps told us contradictory information about whether or not there was a way to cross and whether or not there was a connecting road on the other side. There was no way of finding out beforehand, and so we had decided to try our luck and see, hoping that we did not have to cycle a few days back again. Fortunately, after two days we found out there was a (free) ferry service that brought us to the other side of the Mekong, where for 10 km we enjoyed a perfect tarmac road that connected us to another dirt/dust road to Luang Prabang. Our gamble had been right!

As we mentioned before, we had read about Laos being hilly and having steep roads. Even when we planned our route in our route-planning app Komoot, the extent of warning dark red colours in the climbs should have been concerning. But we played ostrich again and sought comfort in the fact that many times before, roads had looked steep on Komoot, only in reality to be just fine. Not in Laos though! After a “warming-up” in Northern Thailand, 15% gradient-roads were to be our new normal in Laos. The first few days here we found ourselves pushing our bikes over the gravel roads more times than on our whole trip combined. At times we put the blame on the loose gravel and our worn-out tyres that had lost their gripping profile. There was no real going around it though, the roads were just ridiculously steep and they put us and our legs to the test.

A week later, At Muang Ngeun, we joined a newly built connecting road that led us to Luang Prabang. Our legs were desperate for some smoother riding, and we hoped this road would give us some slack. We figured the steep gradients we had faced would mostly be on the gravel roads. Surely, the bigger tarmac roads, would be built smarter as to allow bigger trucks to drive from A to B efficiently. Our relief to be on tarmac was short-lived though, as this road too turned out to be ruthlessly steep and hilly, never giving us a break. Where other countries would lead their roads over sides of hills, using switchbacks to allow vehicles (and cyclists) to climb more gradually, apparently Laos had decided to just cut to the chase and go straight up to the top of a mountain, only to go straight down after it again with the next climb already in view. They sure did not “waste” any tarmac to an extra switchback or two. We joked that the only part of the road that was flat was about 10 m at the top of the climb, just before the road would go down again. So even though we were on a high quality tarmac road, many parts were only doable by zigzagging our way up. We used the whole width of the road doing this – if traffic permitted us – easing the gradient for our legs. What did not help on Sabine’s hand, was the fact that her lightest gear did not work, so she had to push even harder uphill. In Chiang Mai a gear cable had broken, and apparently we had fixed it incorrectly, skipping the first gear. We only noticed this defect in Luang Prabang, after the heaviest climbing was already done!

After nearly two weeks of pretty hardcore cycling and with a huge sense of achievement, we arrived at the charming old town of Luang Prabang. One could easily see the French legacy here in the architecture, the small streets lined with white houses that all had typical French looking roofs. Suddenly, “baguettes” were found everywhere. Although slightly overcrowded with tourists, we enjoyed our time here a lot doing what we mostly do on rest days in towns: walking around, getting lost, and eating loads of good food. In Luang Prabang specifically, we dedicated a lot of our time to the latter, as we had been deprived of it ever since we crossed the border. As mentioned, we hadn’t expected much of the food in Laos, it being much more meat-focussed than other neighbouring countries and a lot less varied. What we had not expected though, was that it would actually be hard to just find any food at times. In many of the tiny villages, the shops literally had not much more than cookies and sodas (and – always – Beerlao). From Huay Xai to Luang Prabang we often had to scramble together some vegetables, ask around for bananas, and go to every shop we passed to finally collect enough for a few meals. In the countries we had cycled through in the last few months, food stalls were found in every tiny village we passed. Somehow that did not go for Laos. More than once, we would pass three villages around lunchtime, our bellies growling from hunger, only to find out that none of these three had a food stall or something to that extent. Fortunately, we had bought a bottle of sweet chili sauce and at those times we resorted to knocking on someone’s door to ask for some plain sticky rice with chili sauce for lunch. Although it’s plain rice, sticky rice tastes really good!

Cycling out of Luang Prabang, we made sure to camp a night close to the famous Kuang Si waterfalls 30 km away. It’s a fairy tale landscape, with many levels of pools filled with crystal blue water and impressive waterfalls. In a few, you are allowed to swim. It might be the most beautiful waterfall we have ever seen. Other cyclists recommended a man with a piece of land a few hundred meters downstream of these waterfalls, who sometimes allows people to camp on his land. We headed off and quickly managed to find Mr. Lee and his beautiful garden. He allowed us to camp right next to the waterfalls and we had another lovely relaxing day. The advantage of camping so close to the Kuang Si waterfalls was that we could enter the park just after opening at 8 AM the next morning, thus avoiding the crowds. It’s a popular tourist attraction, and for good reason. We ended up being the first ones to enter and having one of the most beautiful pools all to ourselves! By the time we made our way out, the park was filled with people. Coincidentally, we bumped into two Dutch motorcyclists, Klaas and Danielle, whom we had met and camped a night with in Tajikistan half a year ago! It was a funny short reunion as each of us headed in different directions.

After leaving Luang Prabang and the waterfalls behind, we aimed for Vang Vieng. This town is renown (or rather, notorious) for tubing – floating down the scenic river on an inner tube from a car/tractor while passing many bars, where the articles on sale range from beers to strong drinks and from hashish cakes to magic mushroom. Yes, the sole reason to participate is to get incredibly drunk. All that came to a halt a few years ago when about 20 people drowned in a single year and the government (finally) closed almost all over the bars. However, our main draw to this place was not getting stupid drunk as to drown ourselves in the river, but rather the stunning karst mountains with huge caves and temples inside and on top of them. Cycling here felt like riding through Avatar country, steep mountains covered in jungle popped out of the earth all around us. It was an impressive sight!

It wasn’t until a few days later that we actually went in one of those caves. And not just any cave; the Konglor cave is a 7 km long cave that you can cross by boat and one of the biggest river-caves in the world. Going through the Konglor cave for us was part of a shortcut of the Thakhek loop. For a few Kip extra, we could put our bikes in the wobbly little motorboats and go through a huge mountain instead of many kilometres around it. Each in our own boat we passed (raced) through the pitch-black cave, passing sites with giant stalagmites and stalactites. Fortunately, we were given strong headlights, allowing us to see how big the cavities were.

Exiting the cave, we were tempted by take a shortcut. On one of our navigating apps, maps.me, we noticed a small track that would save us from quite a bit of climbing and about 30km. Unfortunately, the saying “a shortcut is the longest distance between two points” once again turned out to be true. Conveniently, maps.me forgot to mention there were two rivers to cross and no bridges! The only way to cross the water seemed to be with tiny, unstable wooden rowing boats that lay on the side of the river. The boats were so small and fickle that we had to go back and forth multiple times to get all our stuff to the other side. Although we ended up enjoying ourselves quite a bit with the boats, the worst treat was saved for last. The banks of these rivers were made of a slippery layer of mud, that stuck to literally everything. By the time we had crossed the second river, we had a brick of mud of about one kilogram sticking to each of our shoes. Moreover, our wheels had taken so much mud that they became completely blocked. We had to remove all the mud with our hands and some twigs. After claying for another hour, we had removed most of it. By then, the sun had started to go down and so we camped right next to the river. The next day, we had only about 15 km to go until we would reach a bigger road again. In good spirits we started, thinking we would be there in max 2 hours. We started at 8 AM and made it to that road halfway in the afternoon, after getting lost, heaving our bikes over numerous 20-30m high hills through an overgrown, rocky path and a flat tyre.

The Vietnamese border was close by now, we could almost see it. However, we had applied for the visa right before Tet holiday (celebrating Vietnamese New Year) and the Immigration Department would have a week off. Instead of the expected two days, it meant 10 days extra processing our application. By the time we got close to the Vietnamese border, we had a few days to spare. We decided to take a longer gravel road instead of the highway, where we ran into another maps.me adventure that included a bridge, that had broken down a few years before but was still on the map. We had to haul all our stuff down a steep bank, cross the river balancing on a small plank, and lift them up again on the other side, good fun! It was in this part, that we really felt the damage that had been done to Laos during the Vietnam war and the Secret war (conducted by the CIA as a clandestine war prior and during the official US presence in Vietnam). We passed countless places that had been set off with ropes, with a clear sign mentioning danger of UXOs. (“UneXploded Ordnance”). In other places we could clearly see a cavity in a ground. It reminded us of a controlled explosion of those kind of bombs. These bombs were dropped by the US during the Vietnam war, to destroy the supply routes of the Ho Chi Minh trails between North and South Vietnam. Less known is the fact that these bombings were also part of the Secret War the US was having in Laos. Fighting against communism in Laos by training local tribes to fight a guerrilla war, this quickly expanded to more conventional warfare, mostly at cost of Laotian civilians. Over the course of nine years, the US dropped over 2 million tons of bombs during 580.000 bombing missions. This equals a planeload of bombs every 8 minutes, 24/7 for nine years in a row. Around a third of the dropped bombs did not explode, and these have killed or injured more than 20.000 people since the bombing stopped. It is estimated that around 80 million still remain unexploded. That’s a very scary number to think of when you see all the kids running around in the small villages. We were extremely careful with wild camping here, only sticking to paths that had clearly been walked on recently.

A few days later and 30 kilometres before the Vietnamese border, close to the town of Nong Chan we still didn’t have our Vietnamese visa. Luckily we found maybe the most beautiful hut of all Laos to spend a very lazy day, close to a river to wash ourselves. We entertained ourselves by watching a Netflix documentary about the Vietnam war, drinking our last Beerlao and watching herds of cows pass us. One day later, the much-expected e-mail that our visas were ready finally came and we quickly made for the border.

We had spent nearly 4 weeks in Laos. The cycling in this country had not been of the easiest, the sights might not have been the most impressive of the whole trip, the food not the best. Still, Laos had really given us the “holiday feeling”, with reasonably carefree cycling. We would miss the “sabaideeeee” from the kids, the bamboo huts (in Vietnam they don’t seem to have many of these), the relaxed people, and we would sure miss the Beerlao. Now, our last southeast Asian country was waiting for us: Vietnam! More about that in our next blog.

Talk to you soon,

Tom & Sabine